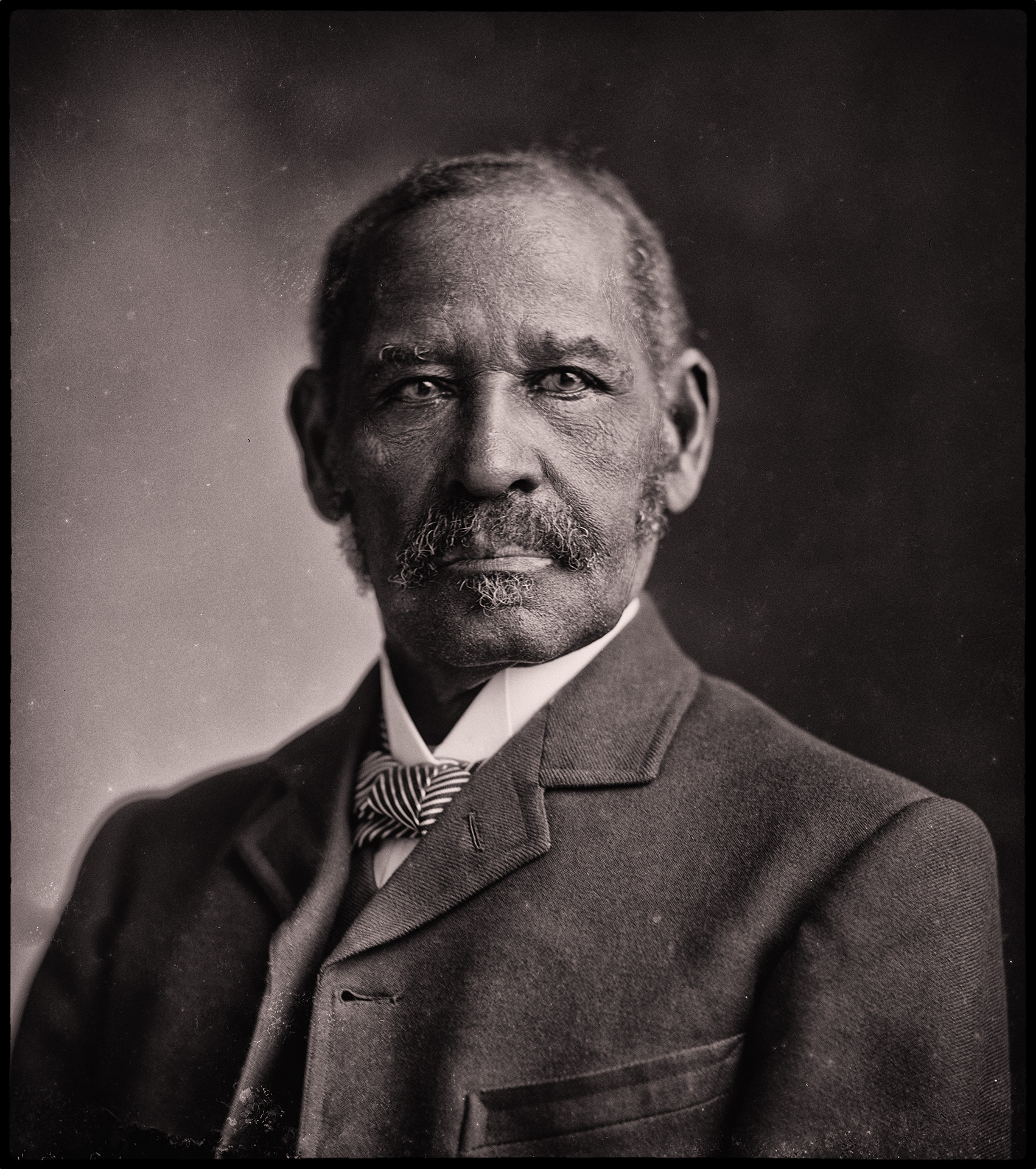

(1823-1915)

Once in Victoria, Gibbs continued his business, having closed up shop and bringing all of his wares to Victoria. Still partnering with Peter Lester, they were able to establish themselves as the first large merchant house in the colony outside of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Aside from the merchant business, Gibbs was able to invest in real estate, develop a coal mine and build British Columbia’s first railroad.

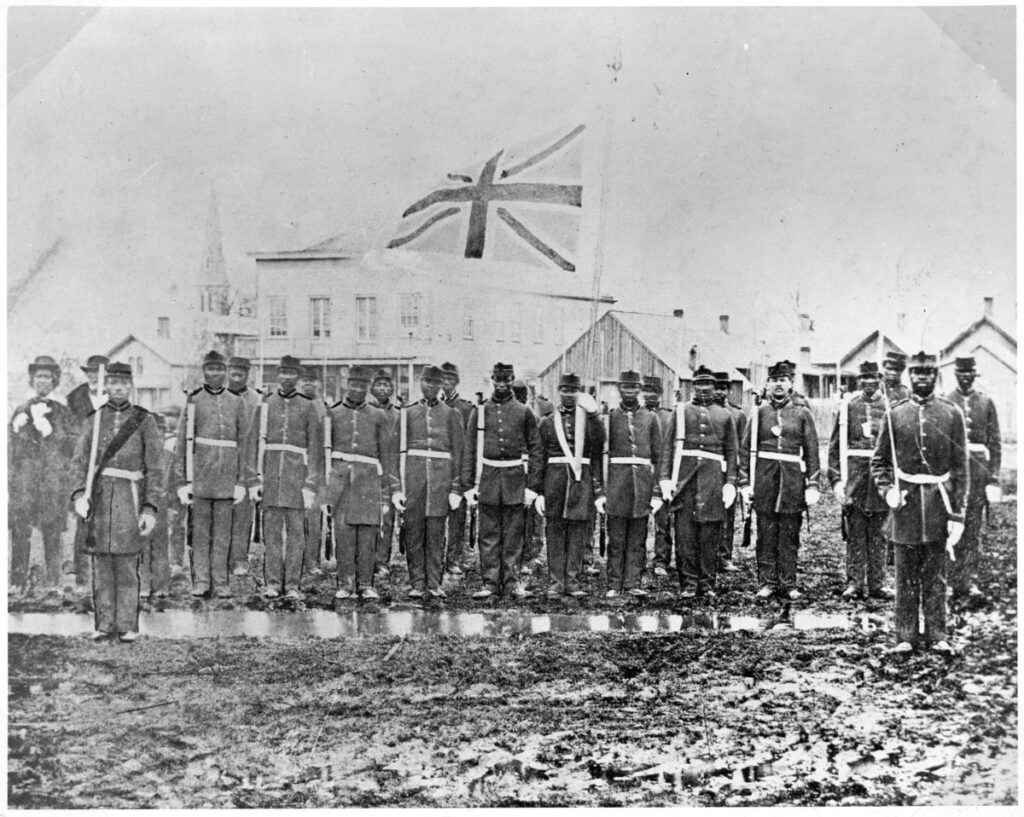

Always an advocate for his people, he helped fund and begin the Victoria Pioneer Rifle Corps, Victoria’s all-black militia and, at one time, Victoria’s only official militia. In 1866, he was elected to the Victoria City Council, the city’s first black councillor. Representing James Bay, he even served as acting mayor at one point. His time in Victoria culminated with being sent as a delegate to the Yale Convention, with the purpose to discuss BC’s entry into Canadian Confederation.

Upon the ending of the Civil War, Gibbs was one of the Americans set to return to the United States and continue his path. He started some legal training while in Victoria, but completed his formal education at Oberlin College in Ohio, an institution that regularly admitted black students since 1835. He settled in Little Rock, Arkansas where he practiced law before becoming the first African-American elected municipal judge in the United States. His final public service position was one of prestige: in 1897, at the age of 74, he was appointed United States Consul to Madagascar by President William McKinley.

After a stint there, he returned to Little Rock and founded the Capital City Savings Bank, became a partner in the Little Rock Electric Light Company, continuing his real estate investments, as well as supporting various philanthropic causes. He passed away at the age of 92.

An extraordinary man, Mifflin W. Gibbs made an impact on the settlement in B.C, and really, anywhere he called home, no matter how short the stay.